Service level objectives (SLO) are standard way of defining the expectations of applications/systems (see SLA vs SLO vs SLI). One standard example of SLO is uptime/availability of an application/system. Simply, put it is % of time the service or application responds with a valid response.

It is also a common practice in large organizations for a SRE team to keep track of SLOs of critical systems and gateway services reporting them to leadership in frequent cadence.

But like any tool, SLO’s also have a motivation and a purpose. Without careful considerations these employing seemingly well intended policies can become a vanity metric and cause unintended consequences. In this post, I take one such situation I encountered in past and provide a simple framework that could help avoid these traps.

4 9’s Availability

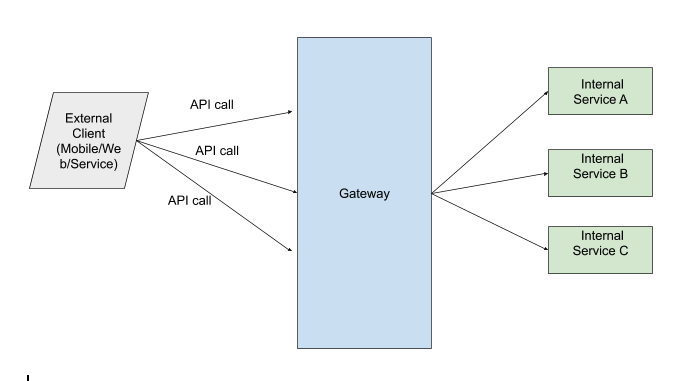

Consider above example which is a common architecture of a company. Usually a gateway service fronts all client/external calls and routes them to internal services. It is also common practice in some companies for a central SRE team to some company level tracks SLO at this gateway level (Note: individual teams still measure their own services’ SLOs).

Today, with commoditized hardware, databases, evolution of container system etc, it has become a common expectation to expect a high uptime of 4 9’s(jargon for 99.99% availability). Simple way this is usually measured is % of Success (2xx in http protocol) responses your application sends with respect to total number of requests. This has almost become a vanity metric for engineering organization. Let us see two classed of problem caused without putting proper thought while defining them.

Lazy Policy Effect

If all you measure is availability across all endpoints as vanity metric, then it is possible that 1 particular endpoint has dominant share of traffic to your service. But does this traffic share reflect the importance of endpoint?

Ex: Let us consider two endpoints.

- Logging endpoint used to capture logs on the device and forward them to backend for analytics purpose.

- Sign-in endpoint used to authenticate user’s session.

It is easy to see how first endpoint can have more traffic and can hide the availability. As SRE team the numbers/SLOs always look good week-over-week if first endpoint is stable.

I call this lazy policy effect. It happens, because at the time of defining SLO’s, it is possible that authors of this policy never asked few critical questions.

- What is the purpose of tracking this SLO? Most often the answer will be – “We need to ensure we are` providing best experience to customers”. Which leads to question #2

- Is this metric truly achieving this purpose? It is clear at this point to see that not all endpoints directly contribute to customer experience. So you probably need a policy which segments endpoints by category (customer facing vs operational etc) and only measures SLOs for relevant ones.

Bad Incentive Effect

Not let see another consequence of these blanket policies.

Let us say 1 of the endpoint’s purpose is to collect sensor logs mobile device periodically. This is most likely a background process which does not interfere with consumer experience on device. In this case, it is easy to see how certain level of failures is acceptable for this endpoint. We can have the device retry on failures or even afford to miss some logs.

But this team unfortunately has to abide by the above 4 9’s policy set by SRE. Otherwise they will contribute to drop in organizational level SLO and will be called into next leadership review to provide an analysis. No matter how well intended and blameless these reviews are, most teams will try to avoid being called into these reviews. There are various “clever” ways you can do that.

One of them, is add multiple retries between gateway -> dowstream service. Or increase timeout duration for calls from gateway -> dowstream service etc. You get the idea.

These will certainly reduce 5xxs (and improve availability SLO). But unnecessarily increased latencies or caused these logging apis take up more resources on the gateway host. This could increase latencies for other “customer” endpoints. Lot of times these are even hard to notice.

Even though organization has defined these policies for better customer experience, they actually degraded customer experience. This might even go unnoticed because the availability SLO is always met.

Aspects to Consider

When defining such engineering policies in organization or team it is important to ask following questions.

Purpose Of THE SPECIFIC SLO

- What is the purpose of tracking this SLO?

- Is this metric truly achieving this purpose and in what situations will this metric not service this purpose?

Second ORDER CONSEQUENCES

- What does it mean for engineering teams to adhere to this policy/SLO?

- What feedback mechanism from teams do we need to put in place (so that we can adapt these policies and not incentivize teams to put work arounds)? Every policy needs to adaptable. Especially policies which demand large organizational cost to adhere to them.