Every manager at some point in their career will be forced to address the question – “Should my team take on more scope or should we continue doing what we do well?”.

The general sentiment around this question often tends to lie oscillate in extremes.

- Growing scope helps your team’s overall output.

- Do what your are doing well. There is a room to improve. Don’t fall into the trap of scope growth.

Unfortunately, for most managers who are faced with this scope situation none of these extremes are useful. In this post, I will dig into why these extremes rarely work and what would be a reasonable framework to address our question of scope growth.

Growing scope to increase output

Some obvious problems with scope growth is the time commitment needed from your team. Time spent in additional scope takes away time from the current commitments, time that could have been spent to improve your oncall health, loss of focus for the team which very likely impacts quality, engineer burn out etc.

An optimist in you might say,” I will get budget for additional engineers which should help with these problems”. Well, you are in for a surprise because output of the team doesn’t always linearly growth size of the team. A lot of factors get in the way. Examples include:

- Your team’s engineering process might not be mature enough to scale to new members seamlessly? These include quality of onboarding docs, code review process, CI tools, stability of code base, maturity of coding & deployment best practices. Without these properly set, you are very likely going to make matters worse and slow everyone.

- Have you accounted for time spent in hiring candidates. This is a cost easy to ignore because it is distributed across multiple people. Your role as manager in sourcing candidate, sell calls etc. 5-8 other engineers interviewing these candidates, time taken to write feedback, follow up debrief meetings. Remember most top engineering companies have an acceptance rate of low single digits. So number of candidates you need to screen for each engineer you want to hire is multiple orders of magnitude. You need ask yourself if your team’s time is better spent somewhere else.

- Onboarding new engineers is a non-zero cost. New engineers are not going to immediately productive. They need to be mentored, they have to familiarize with code base (which means their initial code reviews will demand lot more time from existing engineers), potential for bugs is higher, they need to spend time understanding dependencies etc.

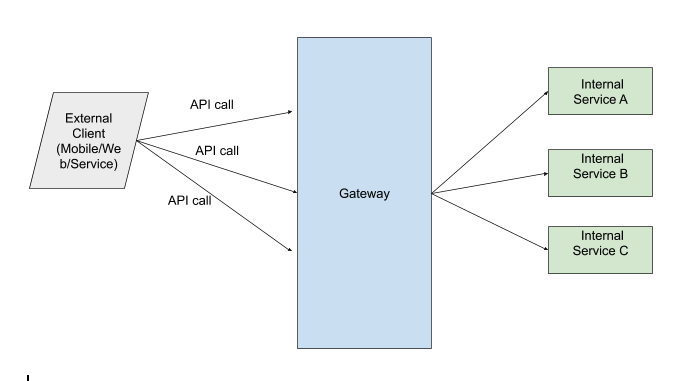

- Can your engineering systems scale to new use-cases?

- Is the new scope/opportunity complimentary to your team’s current portfolio? If not, then you suffer from lack of focus, inability to leverage existing infrastructure, institutional knowledge of the team. Most likely there is a team in your company better suited to do this than your team.

As you can see, if we prematurely grow scope and size of the team, we likely fall short of expectations not only for the new scope but also impact quality of current deliverables, cause likely churn in the team. Now let’s see the other end of the spectrum.

Do what your are doing well

The other end of the pendulum is to continue investing what the team is already doing and possibly. After reading the previous section, it is easy to see why this solution is appealing. But this is not without its faults. Let us look at some of them.

Engineers get better with time and practice

Engineers are humans. So, with practice and time they get good at their job and it is your job as a manager to make sure they do. So, likely what they can handle and deliver in same amount of time will be higher in future.

Engineering Systems get Better

Any good company worth its salt will invest and improve its engineering systems over time. This include deployment systems, engineering frameworks (for logging etc), observability & monitoring, code review tools. Some of these are process improvements within your own team and some could be at company level. But over a period of time, you are hopefully driving towards more productivity in less time. So collectively your team should be able to achieve more in future.

Engineers want to grow

If you are doing a good job of helping your reports long term goals, then some of the junior developers will soon become senior engineers, and some of today’s seniors will want to become leads with larger scope. It is your responsibility as manager to ensure that your are paving the way for these.

Not always will scope grow organically within your product. If you are in a team/suborg where this happens then your job is easier. For majority of the teams, it might not be true. So, you need to be on look out for newer opportunities (which compliment existing charter). Without this, you are likely going impact growth of engineers and possible attrition. Remember that not every engineer will see this problem ahead of time. Even if they do, they might not be comfortable speaking out. It is too late to retain employees once they decide to leave. It is always better to be proactive.

You need to grow

Don’t forget your own growth. As a leader you are expected to self manage your growth to an extent. If you are not constantly looking out for newer challenges, the trap of comfort will soon make you irrelevant and impede your career growth.

Framework for Scope Growth

So we can now clearly see both these extremes are not really helpful. So how do we answer the question – “When to consider scope growth?”. While, the answer is very subjective for every team & company, I found it useful to think about this across two different axis.

Individual level

As a manager you are best position to know the growth trajectory of your reports and how it looks like 6 months from now. So you need to be constantly thinking of opportunities that you can create for them then. For junior engineers these could be new features on existing initiatives (ex: like increased roll outs, new country launches and associated challenges). For senior engineers, this could new initiatives within existing charter of your team/org. You should avoid taking on completely new charters on individual level (exceptions include a very senior engineer or exploratory work).

Team level

At this level you are mostly thinking of newer charter or larger initiatives. There are multiple factors to consider here:

- Maturity of engineering systems: Is your team’s engineering system mature enough to handle new charter. If not, it is better to handle those before considering scope creep.

- Current State of the team: How well is your team executing? In the book Elegant Puzzle: Systems of Engineering Management, the author explain four different stages of team. I highly recommend this framework. I personally found it super useful in determining when to cut or increase scope of a team.

- Composition of team: Always think of the composition of team when considering new charter or initiative. How will this disrupt current team’s execution. Can we take on additional engineers? I personally recommend keeping a lower ratio of newer engineers to existing engineers at any given time.

By constantly thinking in these two axis, we set ourselves & team for good progressive scope growth and hopefully take on new charter and initiatives.

I hope you find this useful. Either way I am interested in knowing your thoughts and learning from your experiences. Please don’t hesitate to leave a comment below.